Click Here for Free Bodybuilding and Fitness Magazine Subscription

Richard Winett HIT Interview

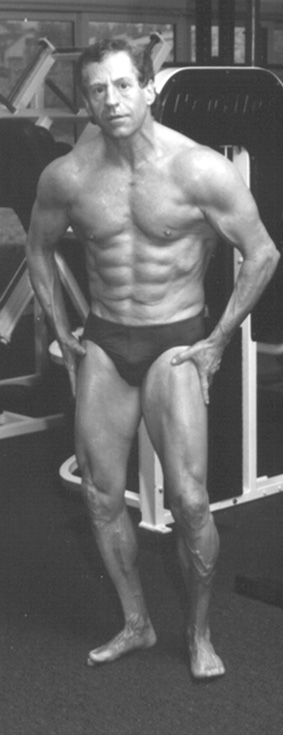

Richard Winett Master Trainer

Dr. Richard A. Winett is the Publisher of Master Trainer and has been a dedicated bodybuilder and weight lifter for more than 40 years. He is is the Heilig-Meyer Professor of psychology and Director of Training in Clinical Psychology at Virginia Tech. He is also Director of the Center for Research in Health Behavior, Blacksburg, VA. He is widely known as an expert in motivation and health behavior, particularly exercise and nutrition. His publications include about 170 professional articles plus several books. The National Institutes of Health and other agencies have awarded him over $10.5 million to support his health promotion and disease prevention research.

By Brian D. Johnston

Brian D. Johnston: Richard, you have an interesting academic background. Tell me about it and how you have applied your skills and education to your current profession and training.

Richard Winett: I'm a professor of psychology at Virginia Tech, a very large comprehensive, major research, state university. I direct the Center for Research in Health Behavior and I also direct the clinical training program. At the CRHB we primarily do large community based intervention trials funded by the National Institutes of Health, although we also do other work and have other sources of funding. Our primary emphasis is helping people change behaviors that put them at risk. We've focused on cancer risk reduction, reduction of risk for heart disease, and the prevention of HIV. I also hope to start research on exercise training, focusing on the principles and routines derived from high intensity training but applying them to average men and women. The goal is to create an extremely cost-effective approach to strength, cardiovascular fitness, and body composition change.

The teaching I do is in health psychology, primarily form a public health approach. I've published about 160 peer- reviewed articles and chapters and a number of books. As far as accomplishments, I'm most proud of the 28 doctoral students that I've chaired to completion at Virginia Tech.

Brian D. Johnston: Are there any specific books you authored that would be of interest to our readers? I recall reading one of your books, which I borrowed from my library about 10 years back, dealing with the psychological approach to athleticism. I found it quite interesting, although the title escapes me.

Richard Winett: The title of the book is Ageless Athletes (1988, Contemporary Press). It's, of course, a bit dated now. The newer content is in my newsletter, Master Trainer.

Brian D. Johnston: On the topic of academia, it's interesting that there appears to be two distinct schools of thought. One, if you don't have a Ph.D., you don't know what you're talking about, and two, people with PhD's don't know what they're talking about. How's that for stereotyping? I find the educational process, scholastically speaking, irrelevant. I've met obtuse and intelligent individuals from both walks of life. One of the most intelligent individuals I know is Greg Bradley-Popovich, who is a promising academic and who writes for our publication. I've also had discussions with some exercise researchers who cannot see the forest for the trees. Mike Mentzer has zero post-secondary training in this field, yet he is one of the few who can apply logic to any situation, including exercise. The same applies to Ayn Rand, who was brilliant in all her thoughts, due to the application of critical thinking fundamentals.

Richard Winett: As in any field, exercise training and the related area of promoting health through exercise have revolved around a particular paradigm, emphasizing as Mike has discussed, the volume of training. As with any influential paradigm, resources and prestige attach to advocating and following that paradigm. Both Ralph Carpinelli and I have done a few short and one very long professional articles that logically show through argument and data some of the fallacies of the approach and some of the misstatements in the Position Stand from the American College of Sports Medicine. The response to these pieces has ranged from indifference to hostility, with one or two exceptions. We haven't given up, though. We're starting to work on another piece. Using theory and data from other studies, We plan on showing that there's little evidence for cardiovascular training that duration is important. Instead, a different mechanism is responsible for adaptation, primarily, intensity of training.

Brian D. Johnston: You don't have to sell me on that last point. Although I rarely do cardio training, with the exception of walking, I used to perform 1 bout of intense stairclimbing for 8-10 minutes every week, and could really tell the difference - particularly in my weight training. The only thing that keeps me from continuing such training is boredom. Perhaps if I had a television set in front of me it would be easier to swallow. How has your training metamorphosed throughout your career? Discuss any particular methods you use to help increase the exactness and specificity of your training.

Richard Winett: The truth of the matter is that I probably would have been

much better off if I just stuck with the kinds of routines I did

as a teenager - basic whole body routines. In any case, that's

what I started with, and at least as far as strength, I was extremely

responsive to training. I made two major mistakes. I started to

do much higher volume training, four to six days per week about

15 sets per body part. This was disastrous. I was constantly sick

and couldn't figure out why. I also got much too heavy, weighing

about 45 lbs more than I do now. The extra weight was mostly fat.

I don't have the capacity to get very large while staying lean

and frankly most people do not have that ability either. It took

me many years to accept that fact and then make the most of my

limitations. I'll discuss that in a moment.

By the early 1970's, I was very influenced by Arthur Jones. His

Bulletins are still classics and while he wasn't right about everything

at that point (particularly volume and frequency), he was right

about many things. I basically trained on high intensity whole

body routines, usually one set of 10 to 15 exercises two to three

times per week. Again, I made some unfortunate mistakes. Given

that these were my 20's and 30's, I wish I could redo those years.

In any case, I was still too heavy. I weighed between 20 to 25

lbs more than I do now. Worse, I was bitten by the running craze,

but even worse, I started to run long slow distance. I didn't

have the sense to see the approach that worked very well for me.

I was doing the whole body workouts two to three days per week

and running shorter distances very quickly. So, instead of just

focusing on running faster, like everyone else, I started running

slower and farther. What a grand waste of time and effort - I'm

getting mad just thinking about it! After about 10 years of that

kind of running, all I had to show for it was that I was weaker

and slower than before I started! So, I lost strength and fitness.

I think if I just kept to my basic weight training approach and just used running the way I now do cardiovascular training, my results on both would have been terrific. I'm a natural sprinter and without any special training could run 400 meters in about 55 seconds. I was also faster at 200 meters. So, the long slow running was exactly the opposite of what I should have been doing. Instead of running 40 miles per week, I could have reduced my cardiovascular training to short interval sessions, two to three times per week for about 10 minutes each session! Each of us has to assess our particular gifts and shortcomings and focus all we have on where our natural abilities lie. That's the one great lesson I learned from all that running.

Toward my late 30's, I started to have a great deal of contact with Clarence Bass and I really focused much more on bodybuilding. I did very well with his periodization programs (Ripped-3) and from a more varied program of cardiovascular training. Considering how I now train, that was a very high volume approach (4 days per week weight training, 4 - 6 sets per body part, body parts trained once hard and once easy each week, plus three 40 minute cardiovascular training sessions). I can tolerate a lot of exercise and improved my strength and appearance on this kind of training.

Brian D. Johnston: I find that interesting, considering you are relatively strong, have a predominance of fast twitch fibers (Richard has an average TUT of 45 seconds or less), yet can tolerate a fairly high volume. This contrasts what many have suspected, that too much volume can result in overuse atrophy in fast twitch muscles. I lean more toward a mixed fiber type (with the exception in my low back, being mostly fast twitch) in most of my body parts, yet can only tolerate 2-4 sets total in a workout, once a week. Apparently there is more to recovery ability than fiber type, perhaps delving into endocrinological and neurological areas.

Richard Winett: I believe there are... as Mike Mentzer discusses, there are vast differences in recovery ability. I always have been able to recover extremely quickly from training. Mike would classify me as a "recovery genius". To pick up where we left off, a big breakthrough of sorts happened in 1990. With Clarence's example and encouragement, I decided to focus on becoming leaner. I had always had a bulky, smooth build and assumed that was my "natural state". It wasn't. All that I did was modestly and consistently reduce calories. I made no other change in my training or diet. Much as Clarence and Mike Mentzer would predict, I slowly but easily lost body fat. I didn't lose any size on my upper body or legs. Most of the fat loss came off my waist and hips. I lost 16 lbs and 6" from my waist, 33" to 27". What a difference. This was really my more natural state and it's been pretty easy to stay close to top condition (e.g., see www.ageless-athletes.com) these last eight years.

For the last four years, my training has been mostly influenced by Mike Mentzer, Ralph Carpinelli, and yourself. Mike's influence was both in theory and practice. He got me most interested in the development of a theory of exercise training that is universal and applies in principle to both resistance and cardiovascular training. Mike also was responsible for the large reduction in training volume that I've followed over the last several years, although he hasn't convinced me that I need to reduce volume and frequency even more. Ralph has provided an incredible education in exercise physiology for me. I now understand that field, certainly not in its entirety, but I do understand basic systems, I know some of the major empirical studies, and I understand the issues. Ralph also got me to switch to much slower repetitions, an approach that has worked very well for me. About two years ago, I believed I had reached some limits as far as resistance and had no where to go. On top of that, I was starting to have some joint problems and some injuries. Using slower reps has given me another productive, possibly, the most productive, way to train. On top of all this, Ralph is a great friend and we constantly talk about all the latest material in exercise science. He also has helped me ( as you have) to have a perspective on training that is a bit more realistic as far as outcomes that can be produced by minor variations in training. In other words, the small things that some of us obsess about in the end, at best, only can result in very marginal differences. You, Brian, have a real scientific grasp of the field and the understanding of a long-time trainee. You're one of the few people writing about the practical realities of the plight of the long-time trainee who has at best very marginal room for improvement. When you write anything, people know it's of high quality and will have some critical take-home point. Brian, this isn't hype, it is exactly what I believe.

Brian D. Johnston: I appreciate your comments, and would like to make a point about long-term training since you brought it up. I don't wish to mention names, since it tends to result in an incredible influx of hate mail and phone calls, but there is one individual who is well known - at least on the internet - who insists we standardize routines. In other words, we should perform the same five exercises, his choices being lat pulldown, leg press, chest press, overhead press and compound row, till the end of time. He rationalized that it is unnecessary to alter exercises for continued progress. Although this may be true - I personally have never stuck with the same program during my 17 years of training to find out - the one important factor he fails to consider is motivation. Without motivation, particularly if the trainee is beginning to dread the same, monotonous routine, how can exercise continue into later years, when exercise is most important?

Richard Winett: I agree with your point. You have to differentiate between an approach and routine that may be theoretically the best from a scientific and physiological perspective and an approach and routine that is firmly based on principles but keeps a person engaged and motivated in the long-term. I've had this kind of discussion a few times about enjoying training vs. following a routine that may be marginally better but that I wouldn't enjoy as much. If training becomes something you dread because the routine isn't suitable for you, all the rest become moot points if you stop training.

Brian D. Johnston: Are there any others who have influenced you?

Richard Winett: Fred Hahn has also been an important influence, if only by constantly challenging my beliefs and training practices. Doug McGuff and his concept and use of time under load has also been extremely important. In fact, TUL and his idea of a single progression system in training guide my current practices. Again, Doug has been influential by challenging my beliefs about aerobic training as well as identifying the exact dose of training that is necessary to produce a response.

Brian D. Johnston: I also believe in the value of TUL. I wrote about it back in 1995 and have used it ever since in my training. I first learned about it while working in a MedX clinic while supervising the progress of clients, and quickly realized its value. Since implementing TUL, have you found that your timing has altered any? In other words, did you reconstruct your routine to match your ideal TULs?

Richard Winett: Yes, more or less with two caveats. As I've noted, I've used the single progression system and as soon as I reach my goal TUL, I increase the resistance. In fact, I try to do this every workout There are problems, though. An advanced trainee simply can not increase endlessly. If that was possible, you would soon be lifting cars and then trucks. There are obvious limits and there are problems in reaching limits so quickly and then constantly hitting your head against a wall as you try to constantly surpass yourself. You've written a lot about this problem and have come up with intelligent alternatives. The second problem is that with a low TUL, I'm starting to get to resistance that is too much for my skeletal system. In other words, I may end up creating the same problems with slower reps that drew me to the approach in the first place. So, I'm experimenting with extending the TUL a bit. It's hard to imagine that somehow a TUL for a muscle group is exact, say 42 seconds. We're simply dealing with an optimal range not a finite number. If extending that range a bit means that training is safer then that's a huge consideration. Again, if you get hurt, making progress is certainly a moot point.

Brian D. Johnston: Yes, without reservation. And your points are well taken, especially as one gets older and the joints get a little more sore and stiff in the morning. I think everyone serious about training should kick butt in the gym for the initial 2-5 years, then slow down and have fun with their workouts. Being hung up on making progress every session, especially in later years, is too demanding mentally. All the really hard work should be done in the initial few years, then a person definitely needs to cycle their intensity/aggression/progress on a motivational level. I won't get into that here as I addressed it in an upcoming book, available February of 1999, entitled Rational Strength Training: Principles and Casebook. How about your current program? Describe it's current design.

Richard Winett: My training program still looks like Mike's HD-1 routine, the every other day three-day split routine. I've done very well on this kind of routine and seem to be getting slightly stronger even at 53 and after all these years of training. Each workout takes between 20 to 30 minutes. After a 10-minute break, I do a very short, very high intensity interval training protocol. Excluding a warm-up and cooldown, the interval training part takes only three to four minutes. I rotate through different cardiovascular training pieces in each different workout. One day per week, I do a 10-minute steady state piece at about 80% maxHR and then launch into the interval protocol. The protocol was developed and tested by Dr. I. Tabata. It's modeled after the training done by speed skaters. I think it's a good match for strength athletes and delivers a big stimulus to the anaerobic and aerobic systems in very little time. I also walk quite a bit, about 20 miles per week. This is mostly recreational. Like many people, my work is totally sedentary and walking is a way to get out and do something. It also helps a lot with weight control if only because you're expending some calories and you don't have to be that careful about how much you're eating.

Brian D. Johnston: I agree with the importance of activity outside of weight training, particularly for the HITer. I walk about 2-3 miles daily on average, except on weekends, and have found it made a vast difference on my weight training. For instance, I can better tolerate 20 rep squats, going to muscular failure rather than cardio failure. Pre-exhaustion is also much easier to tolerate, which is vital for me since I make better progress on super sets and pre-exhaustion than straight sets. I also feel more energetic and functionally capable in my activities of daily living. Most significantly, from a bodybuilding standpoint, neither my leg strength or size has suffered as a result, contrary to what some would have you believe. Of course there's a difference between running 50 miles a week and walking briskly to work every day. Some in the HIT field have made a drastic mistake, suggesting that aerobic activity is unnecessary, that weight training can do it all. The problem is that they're trying to link the new method of HIT, being a few sets once a week, to the old Arthur Jones Westpoint Study. But if you recall, Richard, Jones had his subjects train, I believe, 3 times a week, and a full body workout each time for at least 7-8 sets. And at least one of those workouts called for near zero rest, only enough time to get from one machine to another. As you can see, the volume and frequency are hardly akin. So, to make a comparison is ludicrous and fallacious, putting more myth in the minds of those who look up to supposedly intelligent authority figures.

Richard Winett: I agree with your points. What still is being debated 20 years after the fact is whether or not very high intensity training with minimal time between sets delivers an appropriate stimulus to the cardiovascular system. It may not because weight training may not lead to high levels of oxygen consumption. In any case, you can obtain decent aerobic conditioning from fast walking and as you have found, it enhances weight training and fast walking is safe, convenient, and can be very enjoyable.

Brian D. Johnston: My favorite aspect is that it allows me time to think and ponder over various ideas. Do you find that your training regimen is optimum, at least for you?

Richard Winett: I believe that my current approach to training is the best approach I've followed and that spans about 40 years. The total training time is quite minimal and the results are good. I should add one point because I think it is important. This is the way I enjoy training. I like the challenge of hard workouts and trying to surpass myself. I don't find this approach painful, boring, or uninteresting. Quite the contrary. I love the focus and engagement that is involved. It's hard to imagine training this consistently and this hard for so many years if I didn't enjoy what I was doing. That's an important take home point. Find an approach within high intensity training principles that works for you and is challenging, interesting, and fun.

Brian D. Johnston: Again, I agree, which elaborates on my point about maintaining motivation for longevity. I know of some individuals who prefer not training to failure and increasing the volume slightly (one extra set per body part). Others only train to failure every second or third workout, such as myself. I used to train to failure all the time, but found the mental stress of always bettering myself too demanding, particularly for the amount of progress I made, such as a few pounds every workout, or an extra rep. Interestingly, since I became more relaxed, and haven't pushed myself so hard, I'm really enjoying my workouts, and have made some appreciable gains as a result of my new mind set... and my physique tends to look a bit better. In general, I am not against high volume or periodization if the individual wishes to train in that fashion. What do I care if Joe Smith wants to train for 2 hours each day? Consequently, there appears to be a possible division between an optimum workout and a workout one enjoys. If the two merge, perfect. If they don't, so what? Arnold trained very haphazardly, without any logical or scientific purpose, but he enjoyed it as much as any person could, which is half the battle. I believe he could have made better progress on HIT, but if he detested it, he would not have stuck with it. I used to train in a super slow fashion, even before I heard of the Super Slow Guild, timing my reps for 10/10, and even holding my statics for up to 5 seconds, for a total 25 second rep. This came about due to injuries from 'explosive' type training. But I found this to be mundane, plus it split my focus from the task at hand... that of training hard while maintaining proper body alignment. The last thing I needed was a third factor for consideration. What I'm getting at is, even if a 10/10 protocol was superior to just moving slow - whatever that may be - I would rather make 5% less gains and enjoy my training. However, there are those who enjoy timing their reps and moving for an arbitrary 10/10, which is fine, and ideal for them, making it a viable method.

Richard Winett: I agree completely with your ideas, Brian.

Brian D. Johnston: Briefly, so as not to give away too many secrets, what topics and developments, particularly new and radical ideas, will you be addressing in future issues of the Master Trainer?

Richard Winett: I think the most important pieces coming out are ones involving how to assess your genetic strengths and weaknesses and capitalize on your strengths (and why this process is empowering and liberating) and strategies for advanced trainers. I also try in every issue to have some new information or analysis of studies and issues in health, fitness, and strength.

Brian D. Johnston: I find the genetic analysis proposal to be quite fascinating. Even if everyone wanted to weight train, I think it offers an important wake-up call to ascertain what exactly one is capable of achieving. All too often people have inflated dreams and ideals, such as having 20" arms, or winning the Mr. Olympia. I remember when I bought my first muscle rag, being Weider's Muscle & Fitness, back in the early 80s. I saw an ad featuring Boyer Coe curling with an Arm Blaster. The ad read, "Have you ever seen such mind-blowing biceps?" As with any teenager, the first thought is, "if I could buy that contraption, I could have arms like that!" I also fell victim to Weider's protein drinks, again featuring Boyer Coe. Of course, it never happened, never will and never could with my genetic endowment. But it's crap like that that makes the Weider industry an unnecessary evil. I don't care if this is politically incorrect... but, Joe Weider and all muscle magazines, to a certain extent, have done more to harm the fitness industry than to help it. The amount of mysticism and erroneous information perpetrated throughout the pages, for the past several decades, has been and continues to be so extensive, that we may never be rid of it. Although HIT is popular, it is only popular in terms of 'honorable mentions', debate and ridicule, not actual participation. HITers make up a small percentage of trainees around the world. High volume, senseless pumping still rules and will for some time.

Richard Winett: Unfortunately, I agree with your assessment. What's more, all the magazines now seem to totally revolve around selling supplements and hormones; virtually none of these products have received any testing. The magazines these days have very little information about training, much less sensible training for most people. This is another topic for an extended conversation.

If you have any questions about High Intensity Training workouts, nutrition, etc. Email info@trulyhuge.com